This piece was first published on July 1, 2024, and has been updated since.

What are tariffs?

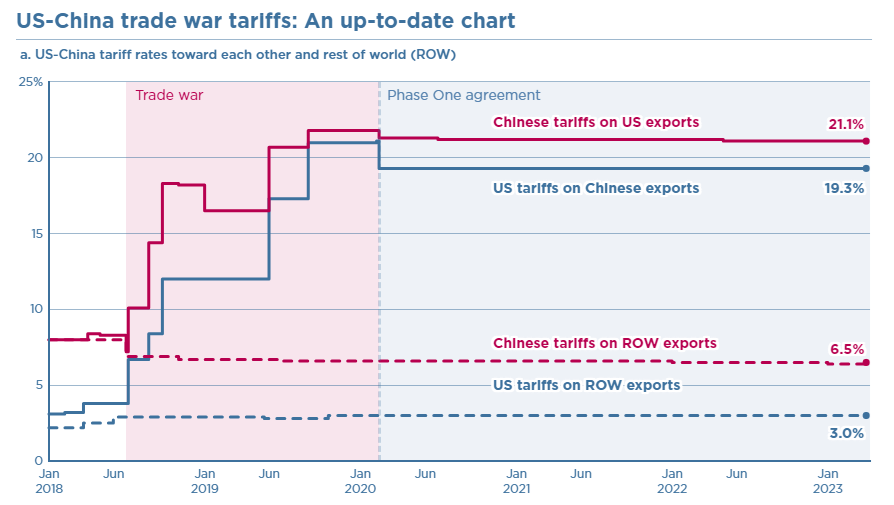

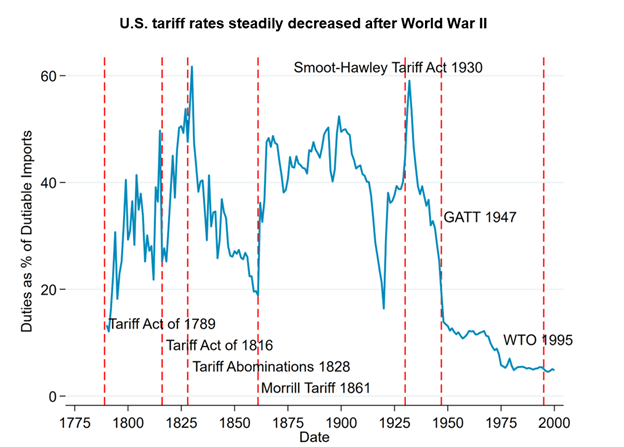

Tariffs are taxes that countries impose on imported goods when they cross the border. From the founding of the United States until 1914, when the federal income tax was introduced, tariffs were the main source of revenue to the federal government. After World War II, the U.S. joined the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) with 22 other countries, which aimed to promote international trade, and began decreasing tariffs. The downward trend in tariff rates continued until 2018, when the Trump administration raised tariffs on several products, especially those imported from China, igniting a trade war. Tariffs on China stopped increasing in January 2020 but have yet to decrease substantially, and remain well above their pre-2018 levels. The Biden administration kept Trump-era tariffs on China in place, and raised them on steel, aluminum, medical equipment, electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries, and solar cells in May 2024. In his first month in office, President Trump imposed a 10% tariff on imports from China, a 25% tariff on all imports of steel and aluminum, and threatened additional tariffs.

Unlike other taxes, which require the consent of Congress, legislation passed in 1934, 1962, and 1974 gives the executive branch substantial to raise tariff rates if it serves a national security interest.

Why do countries impose tariffs?

Among the reasons that countries impose tariffs are to protect domestic industries (particularly those vital to national security), to incentivize foreign countries to change their practices, and to raise revenue. The Trump and Biden administrations said they imposed tariffs for the first two reasons.

Even with the tariffs imposed during the first Trump and Biden administrations, tariff revenues in fiscal year 2024 were about $77 billion, a very small fraction of the $5.27 trillion in total U.S government revenues for that year. The global proliferation of free agreements since World War II has substantially lowered tariff rates, and in turn lowered tariff revenue in wealthy countries, though a number of developing countries still rely on tariffs for a substantial proportion of government revenues.

Who bears the costs of tariffs?

The burden of tariffs can fall on consumers (who may pay higher prices), on importers (who may absorb the cost by reducing their profits and not pass it along to consumers), on exporters (who may absorb the cost and accept lower net prices for their goods), or on some mix of those. Tariffs are often imposed on intermediate goods—goods that are used in the production of things that consumers buy—and this can both erode producers’ profits (unless they find domestic substitutes for those inputs) and raise the prices they charge consumers. Which party bears the heaviest burden depends on the specific market.

A literature review by the Tax Foundation found that U.S. consumers and firms bore the brunt of costs in the recent trade war, with some studies finding partial pass-through (the price increases, but not by as much as the tariff, hurting both importers and consumers), others finding almost complete pass-through (the price increases by the amount of the tariff), and a couple of cases of over-shifting (the price increases by more than the amount of the tariff). They did not find substantial evidence that foreign exporters absorbed the economic burden of the tariffs by lowering prices.

What impact do tariffs have on economic growth?

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) says that the effect of tariffs on output can be ambiguous. On the one hand, some consumers end up buying domestic goods instead of imported goods, and tariff revenues make more resources available for private investment by decreasing the national deficit. These factors increase GDP. On the other, the purchasing power of consumers goes down as goods are more expensive, retaliatory tariffs decrease exports, and some businesses delay new investments out of caution. These factors all decrease GDP.

On balance, economists tend to agree that free trade (low tariffs) increases economic growth more than protectionist trade policy (high tariffs). Free trade allows producers with comparative advantage to get their products to the market cheaply and efficiently, and tariffs get in the way. Additionally, while tariffs may protect infant industries, they can also reduce competition, with adverse effects on an economy. In the 20th century, many developing countries put large tariffs on imported goods using a strategy called “import substitution” to give a country’s domestic industries a leg up until they could compete with advanced countries. In practice, those industries often remained underdeveloped, as they never had to compete with better technology.

Today’s advocates of tariffs say that the textbook models don’t resemble reality because China, in particular, heavily subsidizes key industries and gives them an advantage of over American producers—and could put them out of business altogether, giving China a monopoly.

When the U.S. imposes tariffs on other countries, they often retaliate in ways that hurt the U.S. economy. In January 2025, China, for instance, responded to President Trump’s tariffs by imposing tariffs on U.S. exports liquefied natural gas, coal, crude oil, farm equipment, and some automotive goods.

What are the specific sections of the law that empower the president to impose tariffs?

(This is drawn from a summary prepared by the law firm of Skadden Arps and by the Congressional Research Service.)

- Trade Expansion Act of 1962, Section 232(b) allows the president, after an investigation by the Department of Commerce, to impose tariffs or quotas on imports that threaten U.S. national security. In January 2025, President Trump invoked Section 232 to impose tariffs on steel and aluminum.

- Trade Act of 1974, Section 122 authorizes the president to impose quotas and tariffs of as much as 15% for up to 150 days against countries that have “large and serious” balance-of-payment surpluses with the U.S. This provision has never been invoked.

- Trade Act of 1974, Section 201 allows the president to impose tariffs or quotas on imports of a particular product if the U.S. International Trade Commission finds there has been a surge of imports of that product that cause serious injury to the U.S. industry producing that product. For example, President Trump imposed tariffs on washing machines and solar panels in January 2018 under Section 201.

- Trade Act of 1974, Section 301 authorizes the U.S. Trade Representative to impose tariffs or quotas if it finds that another country has denied the United States its rights under a trade agreement or has engaged in practices that are unjustifiable, unreasonable, or discriminatory and burden or restrict U.S. commerce. For instance, President Biden in May 2024 increased tariffs on Chinese steel, aluminum, semiconductors, and electric vehicles under Section 301.

- The Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA) and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA) authorize the president to regulate all forms of international commerce and freeze assets in time of war (TWEA and IEEPA) or in response to “unusual or extraordinary” international threats to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States (IEEPA). President Trump threatened to invoke IEEPA in May 2019 to impose tariffs on imports from Mexico unless Mexico stemmed the flow of immigrants, but reached an agreement with Mexico before the tariffs were actually imposed. He also invoked IEEPA in January 2025 when he threatened tariffs on Mexico and Canada and imposed them on China. This use of IEEPA could end up in court.

What tariffs did the first Trump administration raise, and why?

The Trump administration argued tariffs were “imposed to encourage China to change [its] unfair practices,” as they were “threatening United States companies, workers, and farmers.” This statement cited a report from the Office of the United States Trade Representative which found that China’s actions “pressure technology transfer from U.S. companies to Chinese entities … deprive U.S. technology owners of the ability to bargain … and support unauthorized intrusions into, and theft from, the computer networks of U.S. companies.” The administration argued in January 2018 that its initial round of tariffs on washing machines was necessary, as increasing imports had hurt American washing machine manufacturers’ financial performance. The tariffs, which made imports more expensive, were supposed to increase domestic purchases of washing machines. Trump’s U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer also argued in July of that year that “China [had] been engaging in industrial policy which [had] resulted in the transfer and theft of intellectual property and technology to the detriment of our economy,” prompting punitive tariffs to spur a change in policy. Trump frequently cited China’s business practices as the cause of the trade deficit between the U.S. and China, saying in June 2018 that “the United States [is] at a permanent and unfair disadvantage, which is reflected in our massive $376 billion trade imbalance in goods.”

China responded to the initial round with retaliatory tariffs. This prompted both countries to continue increasing tariffs for the better part of two years. The U.S.-China trade war paused in January 2020, when the U.S. agreed not to impose planned tariffs on China, and China agreed to buy more U.S. exports. By this point, the level of U.S. tariffs on China had increased from under 5% to over 20%.

What did the Biden administration do with tariffs?

The Biden administration did not reduce any of Trump’s tariffs on China, and in May 2024 raised tariffs on steel, aluminum, medical equipment, lithium-ion batteries, and solar cells.

Biden’s May 2024 tariff increases followed much of the same logic as Trump’s initial 2018 tariffs, albeit without mention of the U.S. trade deficit with China. In its release, the administration argued that “American workers continue to face unfair competition from China’s non-market overcapacity in steel and aluminum” and “encourage[d] China to eliminate its unfair trade practices.” The Biden administration, like the Trump administration, sees tariffs on China as both a punitive measure that might spur a change in Chinese industrial policy as well a way to protect domestic manufacturers.

Though the Biden administration drew criticism from advocates of free trade in both parties for keeping protectionist trade policy, he also has important constituents who want to keep tariffs in place. At the start of his term, the U.S. steel industry, including its union workers, urged Biden to hold steady. In November 2023, Democratic senators Bob Casey Jr. and Sherrod Brown, both from Rust Belt states with many union workers, wrote a letter to Biden arguing that tariffs on steel and aluminum were still necessary.

U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai was asked at a June 2024 event at the Atlantic Council where she agrees and differs with Trump’s former USTR Robert Lighthizer. She said they agree the U.S. has to “change [its] approach to trade,” that she and Lighthizer “share a lot of the same diagnoses” on the U.S.-China trade relationship, and that “one of the ways where Bob and I are most different is in rhetoric.” While many economists and some policymakers in the past have emphasized the benefits of trade to American consumers, Tai and Lighthizer emphasize the risks that trade poses to American workers. For more on Tai’s views, see this interview from Vox.com. For more on Lighthizer’s commentary, see this site, or his 2023 book, “No Trade is Free.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What are tariffs, and why are they rising?

February 11, 2025