In the run-up to President Trump’s inauguration, our expectation was that tariff risk was most elevated for China. There has been a lot of noise since then, but we think developments have validated that view, with the only action—prior to this week—being a substantial, additional tariff imposed on China. We expect the U.S. to raise its tariffs on China still further, which will see China stop “playing nice” and retaliate in a meaningful way, including via depreciation of its currency against the dollar. Steel and aluminum tariffs this week as well as reciprocal tariffs are in our view largely a sideshow. The main show remains China.

What we make of the tariff whiplash

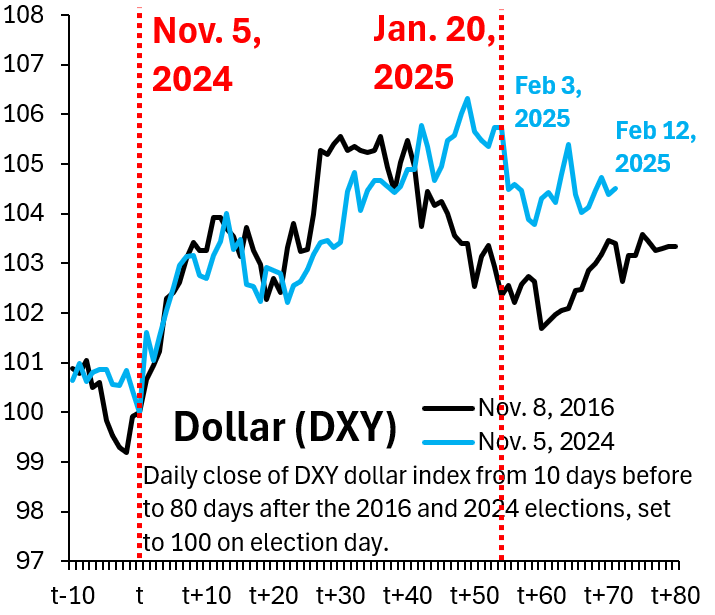

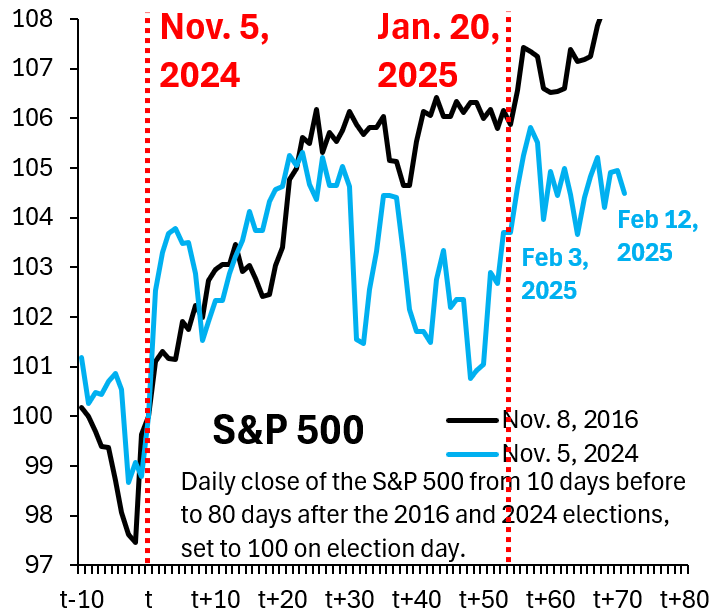

The absence of any immediate measures on January 20 made markets think that tariffs might not be imminent. The dollar fell (Figure 1) and S&P 500 rose (Figure 2) as markets downgraded the odds they placed on an imminent trade war. However, this was followed on February 1 by an announcement of 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico as well as a 10% additional tariff on China. The dollar rose sharply when markets reopened on February 3 and S&P 500 fell, only for the U.S. to “pause” tariffs on Canada and Mexico after concessions on border security. In line with our expectation that the new administration’s key focus is China, only that tariff came into effect on February 4. This week’s steel and aluminum tariffs as well as reciprocal tariffs have left markets unfazed, partly because back-and-forth on Canada and Mexico (and Colombia) fed perception that tariffs are just a negotiating tool.

Figure 1. Daily close of DXY dollar index from 10 days before to 80 days after the 2016 and 2024 elections, set to 100 on election day

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 2. Daily close of S&P 500 from 10 days before to 80 days after the 2016 and 2024 elections, set to 100 on election day

Source: Bloomberg

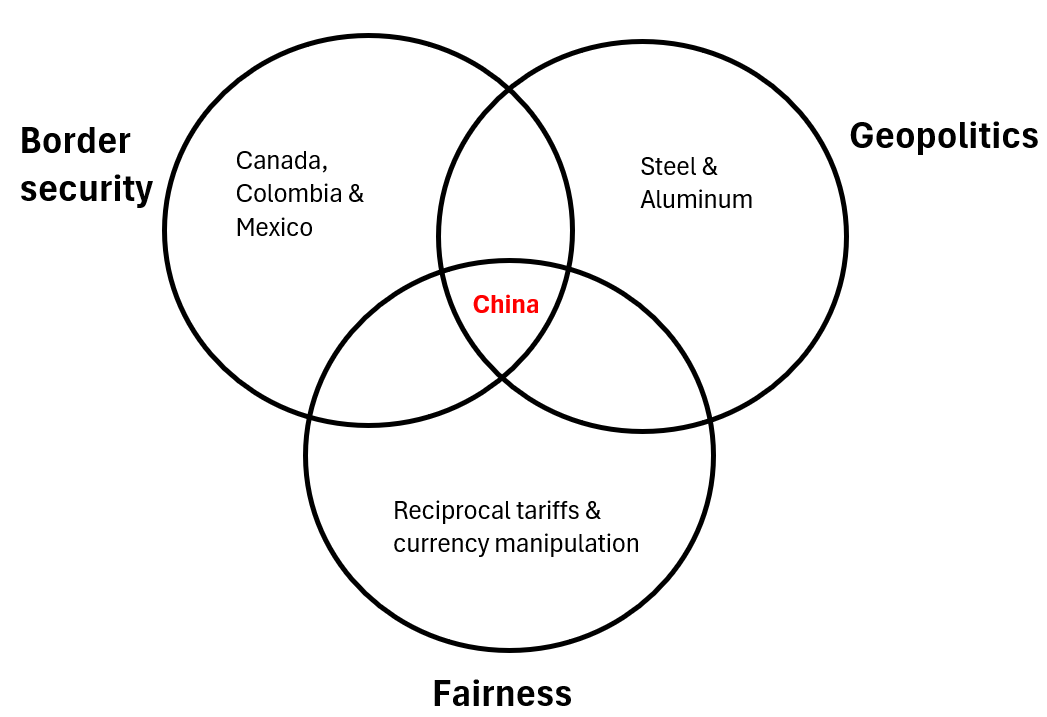

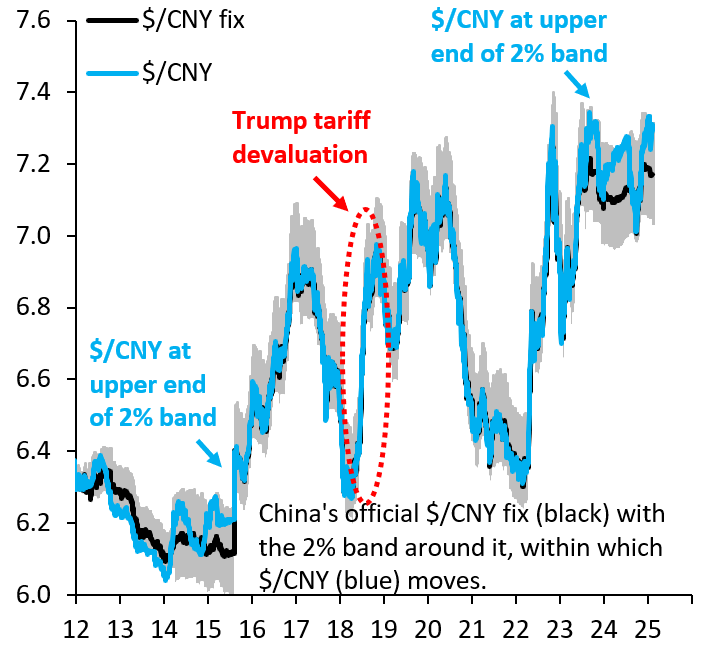

We are only a few weeks into a new administration and uncertainty is high, partly as there are different factions within the administration that hold different views. That said, here is how we think about Trump tariffs, which we think fall into three broad categories: (i) border security, encompassing Canada, Colombia, and Mexico, where tariffs are mostly a negotiating tool; (ii) geopolitics, where steel and aluminum tariffs are part of a plan to secure productive capacity of military transportation and hardware in the U.S.; and (iii) a notion of “fairness,” which encompasses reciprocal tariffs and currency manipulation by China and others in Asia (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Categories of Trump tariffs

Source: Author

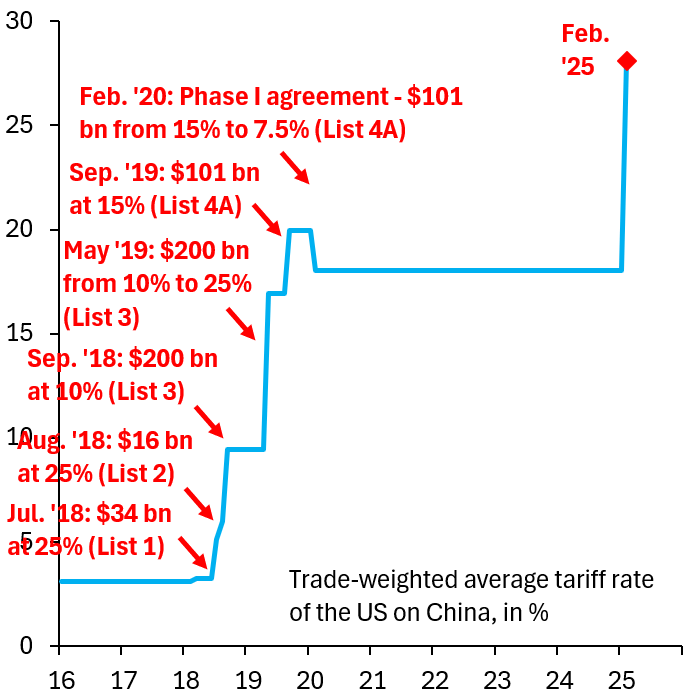

Figure 4. Trade-weighted average tariff rate of the US on China, in %

Source: Bloomberg

We draw several lessons from this taxonomy. First, China touches all three of these categories and is thus central to any tariff debate inside the administration. We think it is no coincidence that—prior to this week’s actions—China was the only country subject to additional tariffs, with the average tariff rate rising very significantly (Figure 4), even factoring in the temporary extension of the “de minimis” exemption. Second, given China’s centrality, we think there is little read-across from on-again, off-again tariffs on Canada, Colombia, and Mexico. Those look to us more like a negotiating tool, intended to exact leverage. That is less true for China, where underlying considerations go deeper, making China tariffs more permanent. Third, there are obviously things like a global auto tariff or a universal tariff that—on the surface—fall outside our three categories. But even here an argument can be made that they fall into the geopolitical or “fairness” buckets.

Figure 5. China’s official $/CNY fix (black) with the 2% band around it, within which $/CNY (blue) moves

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 6. Weighted average effective tariff rates on the US on other countries and of those countries on the US, in %

Source: Haver Analytics

China has so far shown restraint in its retaliation. Announced counter tariffs have been modest in scope, unlike the start of the trade war in 2018, when China matched U.S. tariffs one for one. Perhaps most importantly, China has resisted the urge to devalue the renminbi, merely signaling rising odds that it might do so by allowing $/CNY to move back to the top (weaker) end of the 2% band around the official fixing (Figure 5). China is clearly signaling that it wants to negotiate, even in the face of a large additional tariff, which has come much faster than in the first Trump administration.

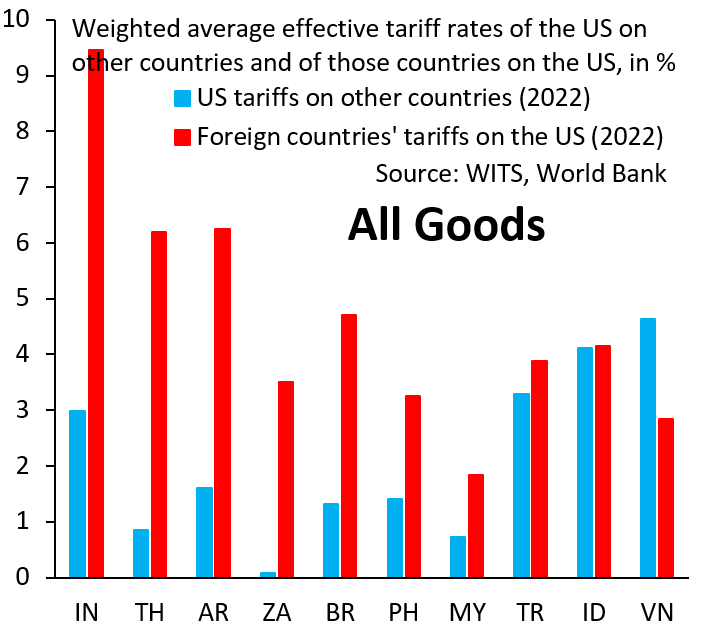

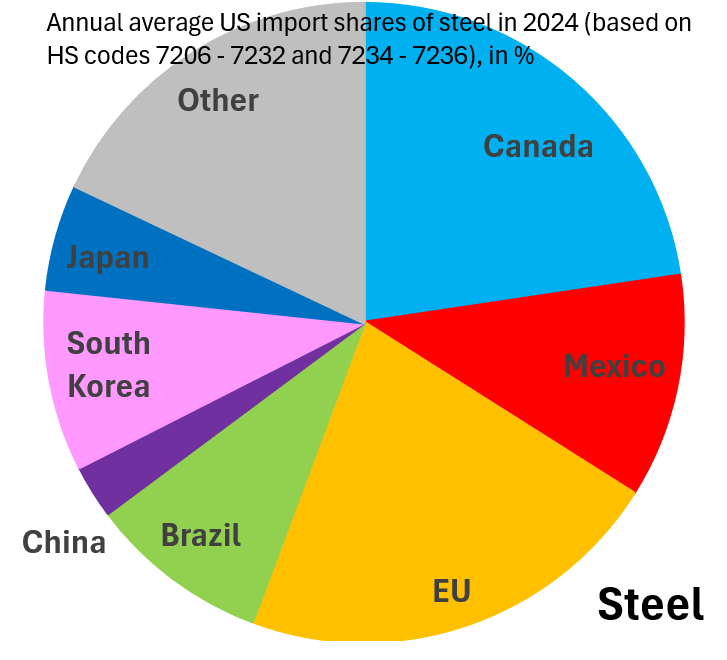

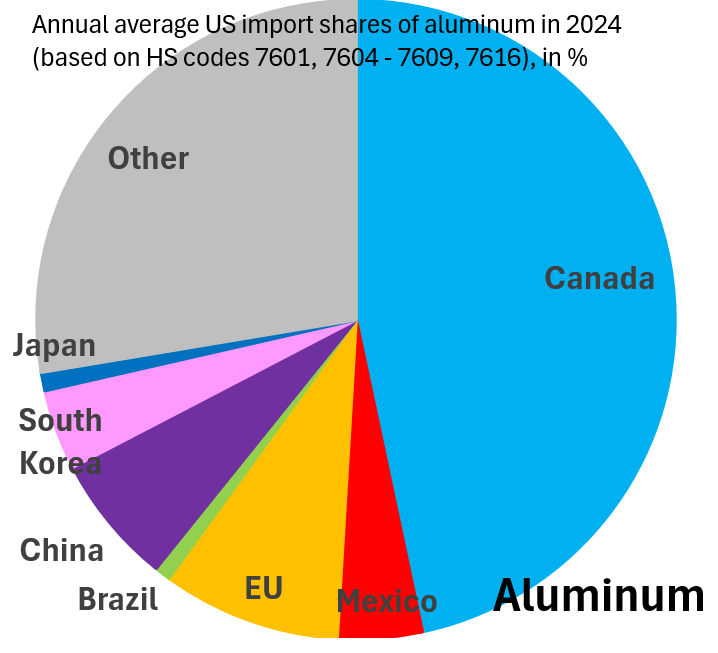

We see this week’s tariff action as peripheral to the main confrontation, which is with China. It is true that foreign countries—especially emerging markets—tariff the U.S. at higher rates on average than vice versa (Figure 6). In our view, reciprocal tariffs will be used primarily as a negotiating tool, forcing other countries to cut tariffs. This is because there is considerable complexity in implementing such tariffs, i.e., whether tariff differentials should be calculated on a product-by-product basis or on a weighted average basis (as is the case in Figure 6). Similar considerations apply to steel and aluminum announcements earlier this week, which rescind prior exclusions and lift the aluminum tariff to 25% (from 10% previously). As Figures 7 and 8 show, these actions primarily hit Western allies, Canada, Mexico, and the European Union, and may again be rescinded if a deal can be struck.

Figure 7. Annual average US import shares of steel in 2024, in %

Source: Haver Analytics

Figure 8. Annual average US import shares of aluminum in 2024, in %

Source: Haver Analytics

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What’s Trump’s plan on tariffs?

February 13, 2025